A growing majority of Hispanics say that discrimination is a major problem preventing Latinos from succeeding, a view most strongly expressed by those born outside the United States. Even so, there has been no change in the share of Latinos who have had a personal experience with discrimination, and fewer today than in 2008 say they have been stopped by the police or other authorities and asked about their legal status.

Perceptions, Experiences and Causes of Discrimination

Perceptions of Discrimination as a Major Problem for Hispanics

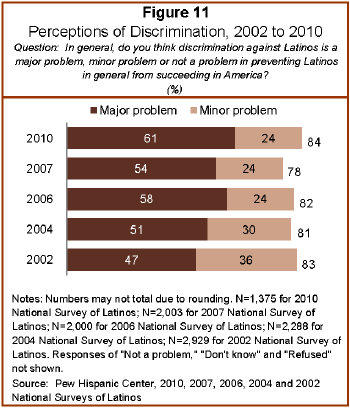

According to the survey, about six-in-ten Latinos (61%) say discrimination against Hispanics is a “major problem” preventing Hispanics in general from succeeding in America, up from 54% who said the same in 2007 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2007) and the largest proportion to say bias is serious roadblock to Latinos since the question was first asked in 2002 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2002). An additional 24% in the latest poll rate discrimination as a “minor problem”; only 13% say it is not a problem.

As Pew Hispanic Center surveys have consistently found, Latinos born outside the United States are much more likely than the native born to say discrimination is a major problem facing Latinos. In the current poll, seven-in-ten (70%) foreign-born Latinos, but fewer than half (49%) of the native born, rate bias against Latinos as a major problem.

Among Latinos born outside the United States, perceptions of bias are most strongly expressed by those who are not legal residents. Among this group, nearly eight-in-ten (78%) see discrimination as a major problem. In contrast, foreign-born Latinos who are legal residents or U.S. citizens are less likely to see discrimination as a major problem (72% and 63% respectively).

Perceptions of discrimination as a major problem for Hispanics have surged among the foreign born in the past three years, yet have remained little changed among the native born. In 2007 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2007), fewer than six-in-ten (58%) foreign-born Hispanics rated discrimination as a major problem, compared with 70% in the current poll. Among native-born Hispanics, less than half three years ago (47%) and in the current survey (49%) rate anti-Hispanic bias as a major problem preventing Hispanics from succeeding in America.

Among immigrant Latinos, those who have lived in the United less than 20 years are more likely to see discrimination as a major problem than those who have lived in this country longer. According to the survey, nearly eight-in-ten foreign-born Hispanics (78%) who have lived in the U.S. for less than 10 years rate discrimination as a major roadblock to Latino progress, compared with about two-thirds (64%) of those who have resided in the United States for 30 years or longer.

Language proficiency also is closely associated with opinions about the impact of discrimination on Hispanics. Three-quarters (76%) of Spanish-dominant Hispanics say anti-Hispanic bias is a major problem preventing Hispanics from succeeding, compared with 57% who are bilingual and just four-in-ten (41%) Hispanics who are proficient in English.

Experiences with Discrimination

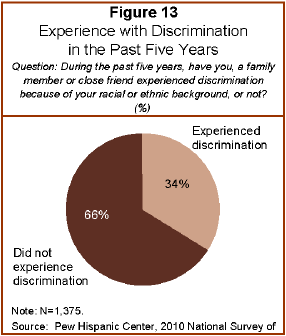

About a third of all Hispanics (34%) say they, a member of their family or a close friend have experienced discrimination in the past five years because of their race or ethnic group. This is largely unchanged from 2009, when the figure stood at 32% (Pew Hispanic Center, 2009), but down from 41% who said the same in 2007 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2007).4

Equal shares of native-born and foreign-born Latinos say they or someone they know have experienced discrimination in the past five years—34% and 33%, respectively. Among the foreign born, 35% of those who are naturalized U.S. citizens, 32% of those who are legal residents and 29% who are neither legal residents nor U.S. citizens say they or someone they know have experienced discrimination in the past five years.

Young Latinos are most likely to say they or someone they know has experienced discrimination. Four-in-ten (40%) of those ages 18 to 29 say this, compared with a third of those ages 30 to 49 (34%) and those ages 50 to 64 (32%). Among Latinos ages 65 or older, fewer than two-in-ten (17%) say they or someone they know has experienced discrimination in the past five years because of their race or ethnic group.

Causes of Discrimination against Latinos

When asked which of four factors—immigration status, language skills, skin color, and income and education levels—is the biggest cause of discrimination against Hispanics, more than a third (36%) choose the immigration status of Latinos. Somewhat fewer Hispanics (21%) say skin color is a major reason for discrimination against Hispanics, while smaller shares say language skills (20%), or income and education levels (17%).

Regardless of Hispanics’ nativity or personal legal standing, immigration status ranks as the single most frequently mentioned cause of anti-Hispanic bias among the four factors tested in the survey. Roughly equal shares of the native born (36%) and foreign born (37%) say immigration status is the biggest cause of discrimination against Hispanics. Some modest differences emerge among the foreign born depending on their residency status. Four-in-ten (40%) Latinos who are not legal residents and 39% of the foreign born who are legal residents say immigration status is the major cause of discrimination against Hispanics. Among the foreign born who are naturalized U.S. citizens, a third (34%) say the same.

Deportation and Detainment

Deportation Worries

At a time when unauthorized immigrants to the United States are being deported in record numbers,5 a majority of Latinos (52%) report that they worry that they, a family member or a close friend could be deported—including 34% who say they worry “a lot.”

Not surprisingly, there are sharp differences in the level of worry about deportation by the nativity of respondents. The foreign born are more than twice as likely as the native born to say they have this concern—68% versus 32%. Most worried of all are the foreign born who are not citizens of the United States and who are not legal residents; among this group, 84% say they worry about deportation.

Large differences also exist between those who speak Spanish mostly and those who speak English mostly. Nearly three-in-four (73%) Spanish-dominant Latinos say they worry “a lot” or “some” about deportation—almost four times as large as the share (19%) of English-dominant Latinos who say they worry that they or someone they know could be deported. Among bilingual Latinos, half (51%) say they worry about deportation.

There has been very little change on this question in the three years that it has been posed in Pew Hispanic Center surveys. In 2007, 53% of respondents said they worried a lot or some about deportation (Pew Hispanic Center, 2007); in 2008, 57% said so (Lopez and Minushkin, 2008); and this year, 52% say so.

Familiarity with Detainment

When it comes to deportation, worry is one indicator, and firsthand familiarity is another. One-third of Latinos (32%) say they know someone who has been deported or detained by the federal government in the past 12 months. Two-thirds (68%) say they do not.

Here, too, there are differences by nativity and immigrant status, but they are not as pronounced as they are for the question about deportation “worry.” Some 28% of native-born Latinos say they know someone who has been deported or detained in the past year, compared with 35% of the foreign-born and 45% of the immigrant Hispanics who are not U.S. citizens or legal residents.

In recent years, deportations of unauthorized immigrants have risen to record levels—just under 400,000 a year in fiscal years 2009 and 2010, according to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.6 About half of all recent deportees are convicted criminals, and many have been removed as a result of new federal-state enforcement partnership, Secure Communities, that identifies and deports unauthorized immigrants from among the population of convicted criminals in state prisons and local jails. In addition, in recent years the federal government has partnered with state and local authorities through its 287(g) program in 26 states to train police on how to determine the immigration status of people they lawfully stop and suspect are in the country illegally.7

Despite the sharp rise in enforcement policies of this sort in recent years, only a small share of Latino adults—just one-in-twenty—say that in the past year they were stopped by police or other authorities and asked about their immigration status, according to the new Pew Hispanic Center survey.

There are no differences on this question by the nativity of the respondent; 5% of both native-born and foreign-born Hispanics say this has happened to them in the past year. There are differences by gender, however: 8% of Hispanic men say they have been stopped asked by police or other authorities about their immigration status in the last year, compared with just 2% of Hispanic women.

When this same question was posed on a 2008 Pew Hispanic Center survey (Lopez and Minushkin, 2008), some 9% of respondents said they had been stopped in the past year by police or other authorities and asked about their immigration status. As in the current survey, there were no differences then in the responses of native-born and foreign-born Hispanics. So at a time when passage of a new law in Arizona8 has touched off a heated national debate over whether Hispanics are being unfairly targeted by aggressive state and local police enforcement of immigration laws, the new survey suggests that the number of Hispanics actually stopped by police and asked about their immigration status has been on the decline over the past two years.

Satisfaction with the Direction of the Country and Their Lives

Satisfaction with the Direction of the Country

Slightly more than a third of all Hispanics (36%) say they are satisfied with the current direction of the country, while 57% say they are dissatisfied. Despite these relative low levels of satisfaction, the proportion of Hispanics who are positive about the nation’s progress has bounced back since July 2008 when only 25% were satisfied with way things were going in the country (Lopez and Minushkin, 2008).

Moreover, Hispanics are more upbeat than all Americans about the course of the nation. Only a quarter (25%) of the general public—11 percentage points below Hispanics—reported in late summer being satisfied with the way things in the country were going (Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 2010b). Since the question was first asked by the Pew Hispanic Center in 2003 (Suro, 2004), Hispanics have nearly always been more positive than non-Hispanics about the direction of the country.

Among Latinos, relatively few differences emerge. Native-born Latinos are somewhat more positive than the foreign born about the nation’s course (39% versus 34%). Among the foreign born, roughly similar proportions of naturalized citizens (34%), legal residents (31%) and Latinos who are not legal residents (35%) say they are content with the way things are going in the United States.

Significant differences among Latinos emerge, however, when these results are broken down by age and the length of time an individual has lived in the United States.

Middle-aged Latinos are significantly more negative about the way things are going nationally than older and younger Hispanics. According to the survey, only a third (33%) of Latinos ages 30 to 49 and 27% of those ages 50 to 64 are satisfied with the direction of the country. In contrast, fully 45% of young adults 18 to 29 and nearly as many (40%) Latinos 65 and older are content with the way things are going.

Foreign-born Latinos who have lived in the United States less than 10 years are significantly more satisfied with the direction of the country than are those who have lived here 30 years or longer—42% versus 30%.

Satisfaction with the Direction of Their Lives

Latinos are broadly satisfied with their lives. Nearly seven-in-ten Latinos rate the quality of their lives as either “excellent” (24%) or “good” (45%), results that are virtually identical to the findings of a 2007 Pew Hispanic Center survey. An additional 27% in the current poll say they are doing “only fair” while 4% rate the quality of their lives as “poor.”

According to the survey, native-born Hispanics are significantly more likely than the foreign born to rate the quality of their lives as excellent or good (83% versus 58%). Among the foreign born, those who are citizens are significantly more upbeat (66%) than those who are legal residents (53%) or who are not legal residents (48%).

English proficiency is strongly correlated with life satisfaction. Only half (51%) of Hispanics who are Spanish dominant rate the quality of their lives as excellent or good. In contrast, three-quarters (76%) of bilingual Latinos and nearly nine-in-ten (87%) who are English dominant offer positive assessments of their lives.

Younger Latinos and the foreign born who have lived in the United States longer than 10 years are more upbeat about their lives than are other Hispanics. Three-quarters (75%) of all Hispanics ages 18 to 29 rate their lives as either excellent or good, compared with more than six-in-ten adults who are 50 or older.

Among Latinos who were born in another country, slightly more than half (52%) who have lived in the United States less than 10 years express overall satisfaction with their lives. In contrast, more than six-in-ten Latinos who have lived in this country for 20 to 29 years (63%) are upbeat about their lives, as are 60% of those who have lived in the U.S. for 30 years or longer.